Education

Understanding Homelessness

Definitions & Hidden Homelessness

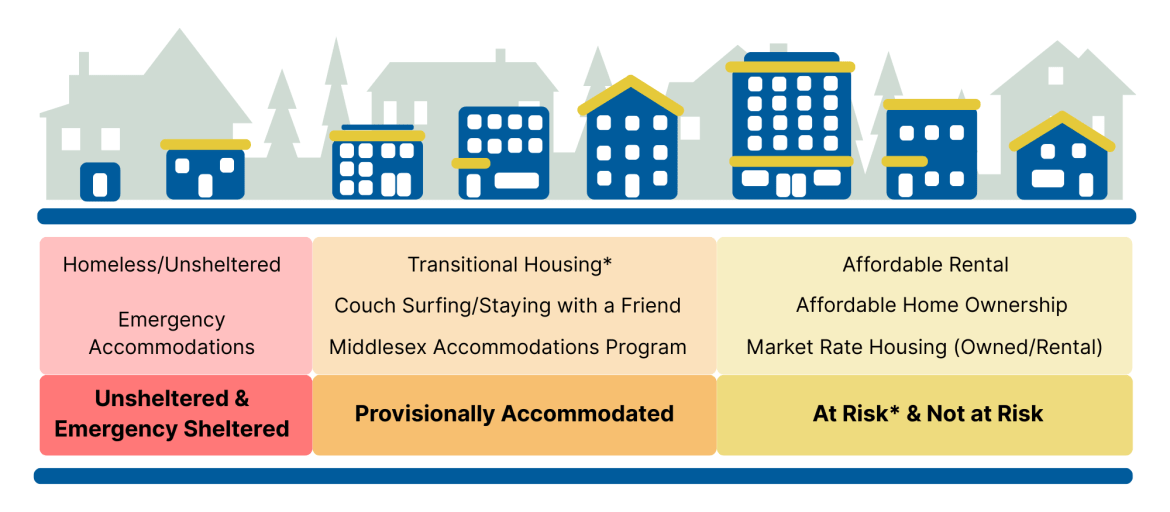

Defining Homelessness and Language - The Spectrum of Homelessness & Housing Continuum

The national definition of homelessness also notes that individuals who become homeless can experience a range of physical living situations, including being:

Unsheltered: Absolutely homeless, living on the streets or in places not intended for human habitation (e.g., living on sidewalks, squares, parks, vehicles, garages, etc.).

Emergency Accommodated: People who are staying in emergency accommodations due to homelessness or family violence.

Provisionally Accommodated: People with an accommodation that is temporary or that lacks security for tenure (e.g., couch-surfing, living in transitional housing, living in abandoned buildings, living in places unfit for human habitation, people who are housed seasonally, people in domestic violence situations, etc.).

At Risk of Homelessness: People who are not currently homeless but whose economic and/or housing situation is precarious or does not meet public health and safety standards (e.g., people who are one missed rent payment away from eviction, people whose housing may be condemned for health, by-law, or safety violations, etc.)

Reference Footnote: (Canadian Observatory on Homelessness, 2012).

Directly from the housing and homelessness plan - A housing spectrum represents the range of housing types required to establish and sustain safe, healthy, and inclusive communities. Safe, healthy, and inclusive communities have a wide variety of adequate housing choices available that reflect the unique needs of the community. Addressing London and Middlesex’s housing shortage requires careful consideration of the entire housing spectrum.

<To keep this more local to Middlesex, we can reword or wait until the new homelessness plan is released to update the graphic description.>

Types of Housing

- Homeless: Living outside, in a vehicle or couch surfing

- Emergency Accommodations: Temporary accommodations for those who are homeless

- Transitional Housing: Temporary housing that provides support services to help individuals move towards more stable housing.

- Social or Subsidized Housing: Affordable rental housing for low-income individuals and families, often supported by government programs.

- Affordable Rental Housing: Rental housing that meets the needs and budget of individuals and families

- Affordable Home Ownership: Ownership that meets the needs and budget of individuals and families

- Private Market Rentals: Rental housing available at market rate without subsidies.

Indigenous "Homelessness"

Indigenous Homelessness

Indigenous homelessness, more recently termed “houselessness,” considers the traumas imposed on Indigenous Peoples through colonialism. Indigenous houselessness is not only defined as lacking a structure of habitation; rather, it is more fully described and understood through a composite lens of Indigenous worldviews, including: “individuals, families, and communities isolated from their relationships to land, water, place, family, kin, each other, animals, cultures, languages, and identities” (Thistle, 2017).

Reference: Thistle, J. (2017). Indigenous Definition of Homelessness in Canada. Toronto: Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press.

Understanding the Duration of Homelessness Experiences

“Understanding the Duration of Homelessness Experiences”

Calgary Homeless Foundation Website, reference footnote to be added at the bottom.

Chronicity is the length of time a person spends in homelessness. There are three types:

- Chronic homelessness

A person experiences chronic homelessness when they have been continuously homeless for at least one year or have had at least four episodes of homelessness in the past three years.

To fall into this category, a person must be sleeping in an emergency shelter or a place not designed for human habitation.

- Episodic homelessness

A person experiences episodic homelessness when they have been continuously homeless for less than one year or have had fewer than four episodes of homelessness in the past three years.

Like chronic homelessness, a person must be sleeping in an emergency shelter or a place not designed for human habitation to fall into this category.

- Transitional homelessness

A person experiences transitional homelessness when they have been continuously homeless for the first time for less than three months or have had less than two episodes in the past three years.

To fall into this category, a person can be sleeping in an emergency shelter, a place not designed for human habitation, a friend’s couch or in a hospital or prison.

Reference Footnote: (Calgary Homeless Foundation, 2025)

Spectrum of Homelessness & Housing Continuum

Housing Continuum

Character Profiles

Profiles of Housing Insecurity Experiences

- At-risk individuals may not realize they are housing insecure/precarious. They may experience challenges such as feeling that their rent or mortgage payment is too high for their income, or living in a home that needs major repairs, or requires financial support to maintain their amenities, such as heating and water. Additionally, they may live in an overcrowded home or cannot find affordable and adequate housing to match their needs, such as needing more bedrooms or accessibility features, due to the low availability of housing options within the community.

- Provisionally Accommodated individuals may find themselves spending more than 30% of their monthly income on housing and actively report not having enough income to support their basic expenses, such as food, clothing, medical, and housing. These individuals may experience employment instability, threats of eviction, a sudden health challenge or conflict in the home, such as rejection due to identity, lifestyle, financial strain, etc, which may lead them to accessing alternative accommodation supports, staying with a family member or friend. Additionally, these individuals may also have to borrow money, access financial support, or other support services to help make ends meet.

Emergency Accommodated or Unsheltered individuals typically face layered challenges that add to their already complex housing and shelter experiences, like the examples listed above. In addition, these individuals may circulate between different housing situation types; they may be able to couch surf for a time, stay in a motel or hotel if they can afford the personal expense, or access an accommodation program if support is available. Other times, they may need to rely on taking refuge in a vehicle, tent, or other places that are not appropriate or healthy for residency, such as taking shelter under bridges, in parks and forests, abandoned buildings or shacks that are unfit for human habitation. Some individuals have spent the majority of the previous year either homeless or in transitional housing.

Disclaimer: It is important to highlight that homelessness and experiences of housing insecurity can happen to anyone, at any time, for any reason. Homelessness and housing insecurity are often layers of complex situations or events that build upon one another, further adding to the difficulty of trying to reestablish a safe and secure housing situation.

- Indigenous Homelessness

Indigenous homelessness, more recently termed “houselessness,” considers the traumas imposed on Indigenous Peoples through colonialism. Indigenous houselessness is not only defined as lacking a structure of habitation; rather, it is more fully described and understood through a composite lens of Indigenous worldviews, including: “individuals, families, and communities isolated from their relationships to land, water, place, family, kin, each other, animals, cultures, languages, and identities” (Thistle, 2017).

Reference: Thistle, J. (2017). Indigenous Definition of Homelessness in Canada. Toronto: Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press.

Myths vs. Facts

See a side by side comparison of common misconceptions surrounding housing and homelessness.

| Myth | Fact |

| Homelessness is only an urban problem. | Homelessness exists in rural communities across Canada. It just looks different. While people may be living on the streets, community members may also be couch surfing, sleeping in abandoned buildings, living in vehicles or homes without heat and electricity, or staying in motels and shelters. It is important to consider the entire spectrum of homelessness, as everyone’s journeys and experiences are different. |

Based on the 2024 Point in Time count, 27 individuals participated in the survey, and an

additional 36 individuals were observed to be homeless. With the addition of individuals

who report having children sharing their housing situation, there are a minimum of 68

individuals who experience housing precarity.

| Myth | Fact |

| Rural communities don’t have homelessness because everyone knows everyone. | Because of the hidden nature of homelessness, you may not be aware of community members who are experiencing homelessness or housing insecurity. In smaller communities, stigma and anonymity often can prevent community members from reaching out. |

Based on the 2024 Point in Time count, only 7% of individuals reported staying with

someone they know for the night of the survey, while 72% reported staying at either a

hotel/motel through a funded program or a transitional shelter/housing.

| Myth | Fact |

| There are plenty of affordable housing options in rural areas. | There are few and limited affordable housing options in rural communities. In rural communities, rental housing is often limited, and at times is in poor condition or too expensive for people to afford. |

| If you’re homeless in a rural area, you can just go live off the land. | No one chooses to be homeless. In Canada’s harsh climate, many people experiencing homelessness suffer from frostbite, physical health challenges and tragically, some lose their lives. |

Sudden and extreme weather situations, such as high temperatures or freezing cold, create

greater challenges for those who are unsheltered, as they often do not have the correct

provisions to ensure their security.

| Myth | Fact |

| Rural homelessness isn’t as serious or urgent. | Rural communities are facing increasing pressures with limited services. As urban systems become overwhelmed, more rural communities across Canada are taking action to provide prevention programs, housing supports, and develop emergency accommodations and supportive housing, often without sufficient funding or support. |

| Rural homelessness statistics are low, so it’s not a big issue. | Rural homelessness is significantly underreported due to data gaps. However, research is emerging that shows that rural homelessness is occurring at per capita rates that are equal to or greater than some of Canada’s largest urban centres (Schiff et al., 2023). |

| Rural homelessness is mostly caused by addiction or mental illness. | While addiction and mental illness may lead to some people experiencing homelessness, people often develop these challenges as a result of the trauma and instability caused by homelessness. Homelessness is driven by a number of complex factors including poverty, the loss of employment, domestic violence or systemic barriers that disproportionately impact marginalized groups. |

Based on the 2024 Point in Time count, the top three reasons reported for housing loss are:

conflict with spouse/partner, not enough income for housing, and conflict with a

parent/guardian.

| Myth | Fact |

| Homelessness is easy to spot. | Homelessness and housing insecurity is often less visible in rural communities due to its hidden nature. People may be staying with family or friends, living in RVs/campers or in unsafe living conditions. |

As reported in the 2024 Point in Time count, the average age at which someone had their

first experience with homelessness was 32 years of age. However, the youngest was 14

years old, and the oldest was 63. This highlights that homelessness can also look different

depending on the individual's age.

| Myth | Fact |

| Homeless people can just move to a city for help. | People experiencing homelessness or housing insecurity have deep ties to their community. Forced migration to access supports in larger cities can disconnect people from their community, social networks and organizations who have meaningful relationships with them. Everyone deserves access to supports without having to leave their home community. |

Based on the Point in Time count, 33% of individuals had reported their previous community

as London, Ontario, demonstrating a migration pattern away from the city for any number of

reasons.

| Myth | Fact |

| Homelessness does not exist in Middlesex County. | Based on the 2024 Point in Time count, 63 people were found to be experiencing homelessness during one night across Middlesex County. |

| People experiencing homelessness or housing insecurity should get a job. | A study in rural Alberta showed that 69% of people who were housing insecure were employed in some capacity at the time they responded to a survey. The reality is there are many barriers preventing people who are experiencing housing insecurity from obtaining a job, including housing, transportation, access to Identification, a phone and a bank account. |

Attainable Housing Review

Learn about the Middlesex County Attainable Housing Review.

Homeless Prevention Plan

Homeless Prevention

Homelessness and housing are issues that affect everyone living in Middlesex County. The Middlesex County Homeless Prevention and Housing Plan ("Plan") commits to addressing housing and homelessness in Middlesex County.

Each plan incorporates the strategies and actions that will guide our work. Housing and homelessness are community issues. The plan calls on all sectors to work together to build solutions and move them to action.

The strength of the plan is to built from the experiences, insights, and ideas of our community partners – individuals and families with lived experience, service providers, funders, advocates, residents, experts, and policymakers. The Plan also builds on the foundational work communities have been doing in Middlesex County to meet the needs of individuals and families.

-> 2019-2024 - Homeless Prevention and Housing Plan

What is happening?

A review of Middlesex County’s Homeless Prevention and Housing Plan is underway and we want to hear from you.

It’s important that the County of Middlesex have a transformational community plan to help guide homeless prevention and housing over the next ten years. The review is an opportunity to identify local community needs and strengthen our overall plan.

Help us update the plan!

Complete a Survey: To share your ideas and insights, complete a survey by November 15, 2024, and invite others to do the same.

Facilitate a Community Conversation: Facilitate a community conversation by November 15, 2024, using the Community Conversation Toolkit, which has everything you need to facilitate a conversation with your neighbours, friends, or colleagues.

The survey and collection of toolkits is now closed, thank you to those who provided your input.

Background

Under the Housing Services Act, 2011, Service Managers are required to review their homeless prevention and housing plans every five years. Local plans must extend for a period of 10 years after the review. The City of London is the Service Manager for London and Middlesex.

Service Managers last reviewed and approved their local plans by December 2019 and are expected to start a review of their local plans in 2024 to meet the requirements under the Housing Services Act.

Therefore, the City of London Housing Stability Action Plan 2019 – 2024 and Middlesex County Homeless Prevention and Housing Plan 2019 – 2024 will both be reviewed through this process. It is expected that the review will result in one comprehensive plan for the County of Middlesex and the City of London.

The plan will be informed by and is intended to complement Ontario’s Homeless Prevention Program, the Government of Canada’s National Housing Strategy and Reaching Home: Canada’s Homelessness Strategy.

This plan will advance the goal of housing stability for individuals and families in the County of Middlesex and City of London.

How will the updated plan be developed?

- Consultation – Opportunities to share insights and ideas will be made available. (September 2024 – November 2024)

- Plan Preparation – The information gathered through the community consultation process will be used to prepare draft strategies and actions. (December 2024 – February 2025)

- Plan Approval – Municipal Councils of the County of Middlesex and the City of London will review and approve the plan. (March 2025 – April 2025)

The timelines may change depending on direction from the Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing.

Want to Learn More?

- Canadian Alliance to End Homelessness

- The Homeless Hub

- Canadian Observatory to End Homelessness

- The Rural Development Network

Homelessness Facts

Homelessness exists in rural communities across Canada. It just looks different. While people may be living on the streets, community members may also be couch surfing, sleeping in abandoned buildings, living in vehicles or homes without heat and electricity, or staying in motels and shelters. It is important to consider the entire spectrum of homelessness, as everyone’s journeys and experiences are different.

Because of the hidden nature of homelessness, you may not be aware of community members who are experiencing homelessness or housing insecurity. In smaller communities, stigma and anonymity often can prevent community members from reaching out.

There are few and limited affordable housing options in rural communities. In rural communities, rental housing is often limited, and at times is in poor condition or too expensive for people to afford.

No one chooses to be homeless. In Canada’s harsh climate, many people experiencing homelessness suffer from frostbite, physical health challenges and tragically, some lose their lives.

Rural communities are facing increasing pressures with limited services. As urban systems become overwhelmed, more rural communities across Canada are taking action to provide prevention programs, housing supports, and develop emergency accommodations and supportive housing, often without sufficient funding or support.

Rural homelessness is significantly underreported due to data gaps. However, research is emerging that shows that rural homelessness is occurring at per capita rates that are equal to or greater than some of Canada’s largest urban centres (Schiff et al., 2023).

While addiction and mental illness may lead to some people experiencing homelessness, people often develop these challenges as a result of the trauma and instability caused by homelessness. Homelessness is driven by a number of complex factors including poverty, the loss of employment, domestic violence or systemic barriers that disproportionately impact marginalized groups.